Fig. 80. 'Our Lady Paramythia'. Wall-painting from the chapel of this dedication in the katholikon, removed from the wall.

Georgios Mantzaridis

There are many miraculous icons and innumerable holy relics on the Holy Mountain; the greatest number of miraculous icons being those of Our Lady, the All-Holy Mother of God. In the Church of the Protaton one may see the icon called Axion estin; at the Monastery of Iveron, the Portaitissa; at the Monastery of Docheiariou, the Gorgoipekoos; at the Monastery of Chilandari, the Tricherousa; and there are others in other monasteries. But the greatest number of the miraculous icons of the Virgin is kept in the Holy Monastery of Vatopaidi: a) Our Lady Vematarissa or Ktitorissa, b) Our Lady Paramythia, c) Our Lady Esphagmeni, d) Our Lady Antiphonetria, e) Our Lady Eleovrytissa, f) Our Lady Pyrovoletheisa, and g) Our Lady Pantanassa.

Our Lady Vematarissa or Ktitorissa (Fig. 3) is located on the synthronon* in the sanctuary of the Monastery’s katholikon and it is connected with the following tradition. In the tenth century, when the Arabs invaded the Monastery, the deacon-monk Savvas was quick to conceal the icon in the well of the sanctuary, together with the cross of Constantine the Great. He even managed to place in front of them a burning candle. This deacon-monk was eventually sent as a captive to Crete. But after 70 years, when he was released and returned as a very old man to the Monastery, he urged Nicholas, the Abbot of the Monastery, to have the well opened, and there they found the icon and the cross upright on the surface of the water with the candle still burning.

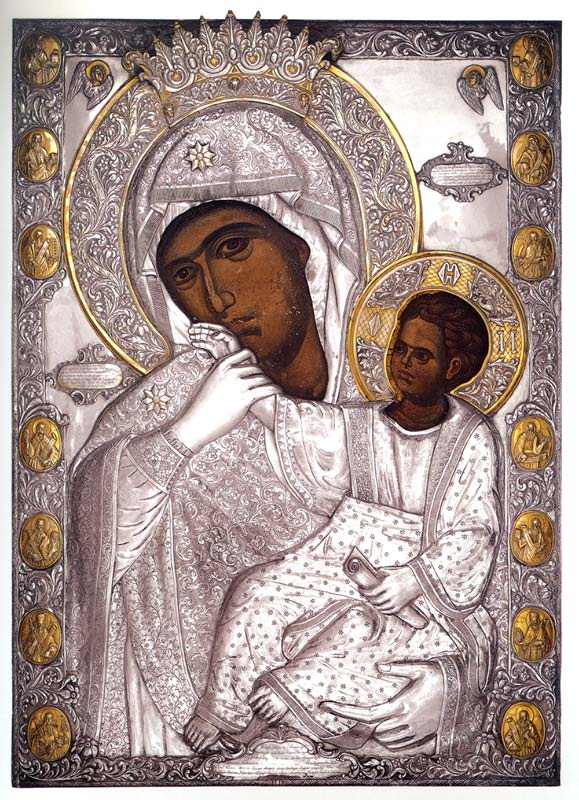

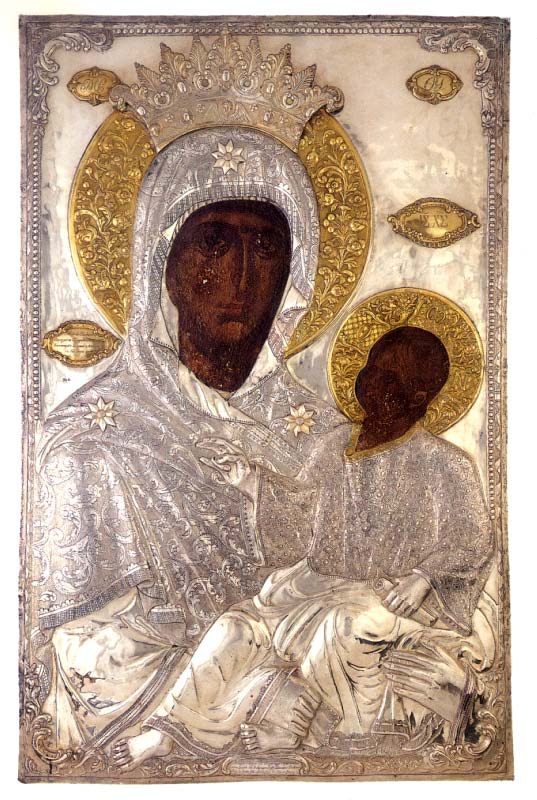

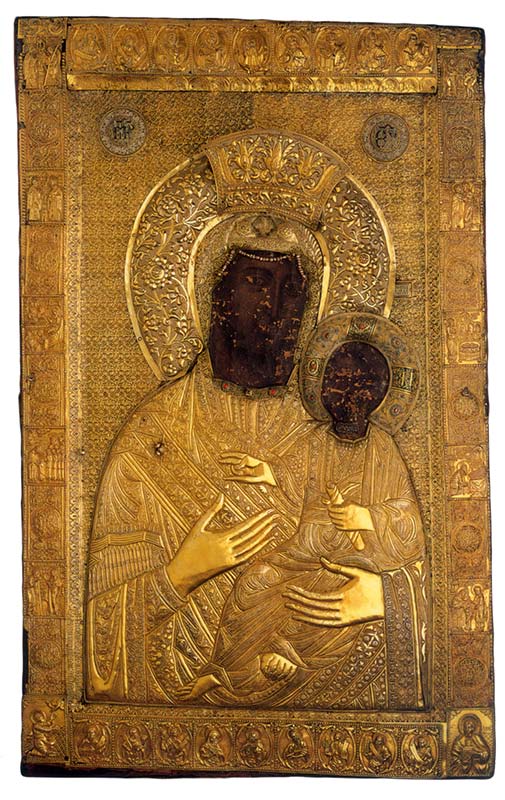

Our Lady Paramythia (Fig. 80) is to be found on the wall of the right hand choir in the chapel which bears the icon’s name. This icon has been removed from a wall-painting in the exonarthex of the katholikon and is dated by tradition to the 14th century. Tradition relates that on a certain day, when the Abbot was handing over the keys of the Monastery to the doorkeeper, he heard from the icon the exhortation that instead of opening the gate the monks must climb the walls of the Monastery in order to repel the pirates. The exhortation was repeated a second time. When the Abbot turned towards the icon, the Holy Infant extended His hand in order to cover the mouth of the Virgin. But the Virgin, taking hold of the hand of Christ and turning her face towards the Abbot, repeated the exhortation. Thereupon the monks sped to the walls of the Monastery and repelled the pirates who had already surrounded it. From that time forth the monks, out of gratitude, have kept a perpetual flame buning before the icon and also chant daily a service of supplication.

Fig. 81. 'Our Lady Esphagmeni'. Wall-painting of the 14th century in the narthex of the Chapel of St Demetrius.

Fig.83.' Our Lady Antiphonetria'. Wall-painting in the corridor between the Chapel of St Demetrius and the mesonyktion of the katholikon.

Figs 84. 'Our Lady Elaiovrytissa': portable icon of the 14th century (28 x 22 cm.) with silver revetment of the same period

Our Lady Pyrovoletheisa is depicted on the lintel of the outer gateway to the Monastery. In April 1822, when a Turkish garrison came to the Monastery, one of the soldiers shot at the icon and a bullet pierced the right hand of the Virgin. Thereupon the soldier lost his reason and hanged himself from one of the olive trees in front of the Monastery, while the rest of the guard were terrified and fled.

Our Lady Pantanassa (Fig. 85), an icon dating from the 17th century, is to be found on the left icon stand in the katholikon. The first miracle wrought by this icon is connected with a certain young man who was involved in black magic. When he entered the church and proceeded to venerate the icon, the face of the Virgin flashed and a powerful force threw him to the ground. The young man was overcome and changed his way of life. To this icon is also attributed healing of many cancer sufferers.

The truth of an icon lies in the person that it depicts. The truth of the icon of the Virgin lies in the person of the Virgin. That is what sanctifies and gives grace to the icon. Old sacred icons, no matter how worn they may be, are never discarded as useless objects, but rather they are either reverently set aside somewhere or are burnt to ashes. They are also used during the consecration of Chrism. Finally, in many instances, when the figure on an icon becomes obscured or even obliterated, the wood, or more generally the surface upon which it has been painted, is used for either a re-painting of the same image or for another icon altogether. There are many icons, even miraculous ones, dating back to very early periods, which survive today either with new, superimposed paintings or as re-paintings.

Matter is not be dissociated from God. It is His creation and it partakes in His creative and providential energy. In particular, that matter which presents the images of sacred persons, the icon, constitutes an object of respect and is “replete with divine energy and grace”1. However, this is not due to its having some distinctiveness in its nature, but because of its relationship with the person represented. An icon does not reveal the nature, it reveals rather the hypostasis of the one who is portrayed. In the icons of the Theotokos, it is not her nature which is revealed, but her hypostasis. For this reason we honour the icon in reference to the person. Every icon of the Virgin is the Virgin because it has her likeness. For this reason on an icon of the Virgin we do not read the attribution: “a representation of the Virgin”, but “the Theotokos”2. According to its nature, the icon is wood, metal, paint, or some other matter. However, in the light of its relationship with the person whom it portrays, it is the Virgin or the image of the Virgin. It is the Virgin as being the namesake of the one depicted, and the manifestation of her archetype3.

The icon operates by the grace of the figure who is portrayed. From this perspective any clear distinction between miracle-working and non-miracle-working icons is invalid. However, certain icons which have manifested very obvious grace and have been linked with specific miracles, are usually designated as miraculous. The grace of these icons establishes a particular blessing which can be linked also with the sanctity of the icon-painters who fashioned them. Moreover, in the Orthodox tradition, the close relationship between prayer and the creation of sacred icons is widely acknowledged. The icon-painters invest, so to say, their prayers in the icons and elicit the grace of the persons whom they are depicting. But even this grace is connected with the person portrayed, and in the final analysis it emanates from God. He it is who performs the miracle, irrespective of whether the request is referred directly to a certain saint4. By this means the person depicted, who refers back to his prototype, keeps open the communication of the believer with God.

The truth of the Church has a hypostatic quality. It inheres in the person and it is made manifest by the person. The features of a saint which are depicted in an icon make his presence tangible. Furthermore, the saint himself, and above all other saints the Theotokos, is a creation “in the image of God”. The affinity of man with God is grounded in the icon. Christ is “the icon of the invisible God”5. Man is a creature whose archetype is Christ. And the relationship of man to God is iconic, that is to say, personal, living, and true. This is why Orthodoxy is identified with the truth of the icons and is celebrated at the feast of their restoration. It suffices for the believer to regard the icon correctly and to be guided by it to the prototype.

The identification of Orthodoxy with the truth of the icons reveals its identification with the truth of the person or the hypostasis. For the Orthodox Church the absolute truth is the Tri-hypo-static God: the invisible God the Father, the Son of God, who is the icon “of the invisible God”6, and the Holy Spirit, who, as an icon “of the Son makes man a dwelling place of Christ by granting to him his hypostasis “in the image of God”7. Man matures as a hypostasis when he approaches the truth of the Tri-hypostatic God through man-made icons. This is why we have icons of Christ as well as those of the Virgin and of the saints. In this way, man, who possesses a body and is unable to relate directly to the spiritual world, is guided to these “for physical contemplation”8.

The natural icon can be distinguished from the prototype by its hypostatic hallmarks. Hence it has its own name. The natural icon of the Father is the Son. And the natural icon of the Son is the Spirit. On the other hand, the artifactual icon differs from the prototype according to its nature and has no significance without it. The name of the artifactual icon is the name of the prototype. The name of the icon of Christ is Christ, of the Theotokos is the Theotokos, etc. And the veneration of honour which is rendered to the icon is addressed to the prototype9. The icon is a ‘locus’ of encounter with the prototype10.

Correspondingly, just as the honour given to the icon is directed to its original, so is any insult offered to it. The miracles with which two of the wonder-working icons of the Monastery are connected are exemplary punishments for abusive acts. Our Lady Esphagmeni punished the one who had wounded her. And when he had demonstrated his sincere repentance, she allowed the abusive act to remain as a stigma with the black, uncorrupted hand. Our Lady Pyrovoletheisa brought the offender to despair. In this fashion not only was the Monastery liberated but the insult was held up to execration. Sacred philanthropy did not nullify divine order.

The Orthodox Church, in addition, greatly honours sacred relics, which constitute tangible evidence of the historical presence of the saints in the world. The Monastery of Vatopaidi is rich in holy relics. They number approximately a thousand items and derive from around 150 saints of the Church. Amongst these, special pride of place goes to the finger of St John the Baptist, the sacred skulls of St Gregory the Theologian (Fig. 86), of St John Chrysostom (Fig. 87), of the martyrs Mercurius (Fig. 472) and James the Persian, of the righteous founders of the Monastery: Nicholas, Athanasius, and Antony and the newly-revealed miracle-worker Evdokimos, and others; pieces of the sacred skulls of Stephen the first martyr, Modestus the priest martyr, Pelagia the virgin martyr, Theodosia the martyr of Constantinople, Charalampus the priest martyr, Sts Se-rgius, Bacchus, Theodore the Commander of Armies, Florus (Fig. 472), Arethas, and others. In addition, the Monastery possesses the right hand of the Apostle Andrew, and of St Macrina, St Panteleimon, St Tryphon, and St Procopius; the foot of the Apostle Bartholomew, and of Saint Parasceva the Younger, St Panteleimon, St Theodore the Tiro, Hermolaus the priest martyr; and a fragment of the right hand of the holy great martyr Catherine, and others.

The saints are Spirit-bearers not only for the period of their earthly existence but also after their death. The grace of the Holy Spirit remains indelibly in their bodies and does not separate itself from their sacred relics11. The relics, however, do not represent a prototype, as do the holy icons, but are tangible remains of the saints’ very bodies. The honour given to the relics of the saints is ho-

Figs 84 and 85 (next double page). ‘Our Lady Elaiovrytissa’: portable icon of the 14th century (28 x 22 cm.) with silver revetment of the same period; and ‘Our Lady Pantanassa’. Portable icon of the 17th century.

nour addressed to the saints themselves. Once again, it is an honour which is directed to their person or their hypostasis. In the case of sacred relics, we do not discern the saints’ forms; instead, it is matter itself that bears their particular grace, for grace resides in their sanctified bodies. And when the believer reverences the relics of a saint with faith and a pure heart, he comes into contact with the grace that dwells in them.

The Orthodox Church ascribes due veneration to those objects that are linked with the saving work of Christ, as well as to any personal possessions of the saints, such as the things which had any connection with their living or dead bodies. It is indeed characteristic that even these are called sacred or holy relics12. In everyday life the objects associated with loved ones, especially with those that have died, are preserved with love and respect. They are understood, in some way, as an extension of their bodies; as things which adorned their bodies. The same applies also to the objects that are associated with the saints. These in the same way are seen as having a link with the saint and are honoured as opportunities of reference to his person. Once more the reason that they are esteemed is the truth of the person. But the Spirit-bearing person opens up new perspectives. For this reason honour here is not fixed purely on the emotional level, a level whose existence is of course quite natural, but also on the ontological level. These objects preserve the grace of the saint because they were connected with his person and his life.

Positions of primacy among the sacred objects which are in safekeeping at the Monastery are held by the fragments of the Life-Giving Wood of the Cross (Fig. 90) and the Reed of the Passion of Christ the Saviour13. Immediately after these comes the Holy Girdle of the Theotokos (Fig. 88), which is one of the rarest relics of her earthly life. According to tradition, the Holy Girdle was made by the Virgin herself from camel hair.

Fig. 89. Reliquary containing the head of St Evdokimos the Newly-Revealed. "At the expense and cost of Gavriil monk of Naousa and Physician of Vatopaidi. 1842 January 10".

Fig. 90. The reliquary and cross, with a large piece of the True Cross, given to the Monastery, according to tradition, by the Serbian noble Lazarus.

Source : Ditomo of Holy Monastery of Vatopedi

http://vatopaidi.wordpress.com/2010/06/24/

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου